Class 12 : English (core) Compulsory – Lesson 2. Lost Spring

EXPLANATION & SUMMARY

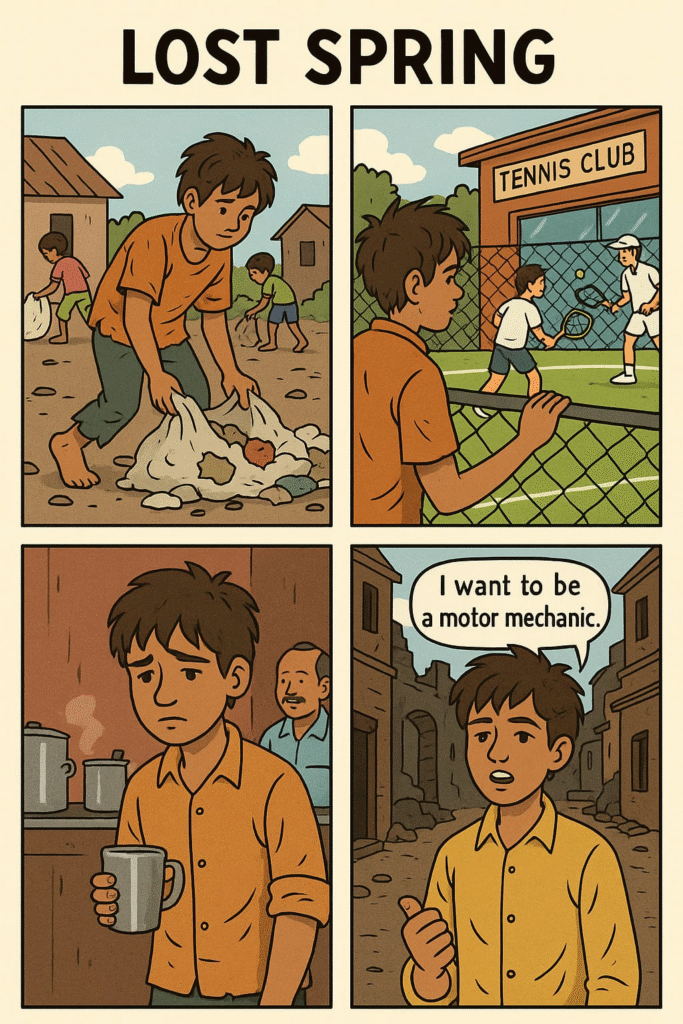

“Lost Spring: Stories of Stolen Childhood” is a poignant narrative that exposes the harsh realities of child labor and poverty in India. Written by journalist and author Anees Jung, the essay is divided into two parts, each focusing on a different child and their lost childhood. Through a journalistic yet empathetic lens, Jung draws attention to the tragic conditions that rob children of the joys and innocence of spring—the metaphor for childhood.

The first part of the essay introduces Saheb-e-Alam, a ragpicker boy from Seemapuri, a settlement on the outskirts of Delhi. Originally hailing from Dhaka, Bangladesh, Saheb and his family migrated in search of a better life after their land was destroyed by frequent storms. Ironically, they ended up living in abject poverty. Seemapuri lacks even basic amenities like sewage, running water, or permanent housing, yet its inhabitants are content because they at least have access to food.

Saheb, a barefoot boy, symbolizes the countless children who are forced to scavenge for survival. When asked why he does not wear shoes, he says his mother doesn’t buy them, and then adds, almost as a defense, that going barefoot is a tradition. This innocent rationalization highlights the normalization of deprivation in poor communities. Saheb once had aspirations of going to school, but circumstances never allowed it. Later, he finds a job at a tea stall. Although it provides some income, he loses his freedom—he is no longer his own master.

The second part of the essay shifts to Firozabad, a town famous for its glass-blowing industry, and introduces Mukesh, another child laborer. Mukesh belongs to a family trapped in the vicious cycle of traditional caste-based occupation. For generations, his family has worked in glass factories under inhuman conditions—amid high temperatures, dark, congested rooms, and without proper ventilation or safety measures.

Jung highlights the systemic exploitation that keeps families bonded to this trade. Despite the government’s laws against child labor, these children work because they have no other choice. The combined forces of poverty, social custom, and apathy of the authorities ensure that these children never escape the shackles of their fate.

Mukesh, however, stands out. Unlike others, he dares to dream. He wants to be a motor mechanic. Though his dream is modest, it’s revolutionary in a community that accepts suffering as destiny. His desire symbolizes hope and resistance against generational oppression.

The title “Lost Spring” metaphorically captures the essence of the essay—childhood (spring) lost to the harsh realities of poverty and labor. Jung’s tone is compassionate and observant. She doesn’t offer direct solutions but compels the reader to reflect on the stolen dreams of these children and the collective failure of society to protect them.

Conclusion

“Lost Spring” is a powerful commentary on the systemic failure that robs underprivileged children of their basic rights, education, and happiness. Through the real-life stories of Saheb and Mukesh, Jung gives voice to millions of children trapped in poverty, urging society to acknowledge and act against this silent suffering.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

PASSAGE

“I ask him if he ever wants to go to school. He points his broom at the distance and says, ‘There is no school in my neighborhood. When they build one, I will go.’ His dark eyes gaze ahead, full of hope. He adds, ‘Garbage has a meaning.’ That’s why he says he likes it. For the children, it is wrapped in wonder; for the elders, it is a means of survival. One winter morning I see him standing by the fenced gate of the neighborhood club, watching young men dressed in tennis whites. ‘I like the game,’ he hums, content to watch it standing behind the fence. He too is wearing tennis shoes that look strange over his discolored shirt and shorts. ‘Someone gave them to me,’ he says, in the tone of an explanation.”

🔍 High-Difficulty Questions and Answers (Class 12 – Flamingo – “Lost Spring”)

(Short Answer – 30 words)

1. How does the boy’s response about school reflect a deeper socio-economic commentary?

Answer:

The boy’s conditional willingness to attend school reveals systemic neglect. His hope is passive, showing how poverty restricts ambition, making even basic education seem like a distant, external possibility.

(Multiple Choice)

2. What does the fence symbolize when the boy watches tennis players from the other side?

A. A boundary between childhood and adulthood

B. A symbol of aspiration and exclusion

C. A safety barrier for the club

D. A decorative element of wealth

Answer:

B. A symbol of aspiration and exclusion

(Fill in the blank)

3. The boy’s statement, “Garbage has a meaning,” signifies that for his community, trash becomes a symbol of both __ and fragmented dreams.

Answer:

livelihood

(Fill in the blank)

4. The boy’s worn tennis shoes, mismatched with his clothes, metaphorically represent the disparity between his lived reality and his __.

Answer:

aspirations

(Assertion and Reason)

5. Assertion (A): The boy enjoys the sight of tennis players but makes no attempt to join them.

Reason (R): He subconsciously accepts his social position and its limitations.

A. Both A and R are true, and R is the correct explanation of A.

B. Both A and R are true, but R is not the correct explanation of A.

C. A is true, but R is false.

D. Both A and R are false.

Answer:

A. Both A and R are true, and R is the correct explanation of A.

(Short Answer – 30 words)

6. What is the significance of the boy’s tennis shoes in contrast with his tattered clothing?

Answer:

The shoes act as ironic tokens of class contrast—symbols of privilege placed in a context of deprivation—highlighting how partial access to wealth cannot erase systemic inequality or exclusion.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

OTHER IMPORTANT QUESTIONS FOR EXAMS

1. Why is the title “Lost Spring” symbolically appropriate for this essay?

Answer:

“Lost Spring” symbolizes childhood lost to poverty and labor. Spring represents innocence, joy, and new beginnings. Saheb and Mukesh, though young, are burdened by survival. Their ‘spring’ is consumed by economic hardship, making the title a poignant metaphor for stolen childhoods.

2. What does Saheb’s acceptance of his job at the tea stall reveal about economic displacement?

Answer:

Saheb’s shift from a ragpicker to a tea stall worker highlights the illusion of progress. Though he earns regularly, he sacrifices autonomy. His life remains constrained by class and necessity, showing how employment can be exploitative rather than liberating in poverty-stricken societies.

3. How does Mukesh’s dream to become a motor mechanic defy his generational fate?

Answer:

Mukesh’s ambition resists the generational confinement of glass-blowing. His desire to break away from caste-imposed labor symbolizes rebellion against hereditary bondage. Unlike others, he dares to choose—a radical act in a community conditioned to fatalistic submission.

4. How does Anees Jung blend journalistic observation with literary sensitivity in the essay?

Answer:

Jung combines factual detail with evocative storytelling. Her observations are laced with empathy and metaphor, allowing readers to emotionally engage with social injustices. She captures poverty’s texture not with statistics, but through intimate, reflective glimpses into children’s interrupted lives.

5. What role does the theme of hope play in the lives of the children depicted in “Lost Spring”?

Answer:

Hope is both coping mechanism and silent rebellion. Saheb finds wonder in garbage; Mukesh dares to dream. Their fragile aspirations stand in contrast to their grim realities. Hope doesn’t solve their problems but gives dignity and resistance to their narratives.

6. Why does the author describe garbage as having “wrapped in wonder” for children?

Answer:

Garbage represents mystery, survival, and unpredictable joy. To children like Saheb, it is more than refuse—it is a treasure trove where dreams flicker amid decay. The phrase reflects their innocence and resilience in redefining what is otherwise discarded by society.

7. What does the phrase “his world is governed by chance, not choice” reveal about Saheb’s life?

Answer:

It shows the randomness that governs lives in poverty. Saheb’s future depends on what he finds in garbage, not what he chooses. His life lacks structured opportunity, making chance his only consistent force, and highlighting deep systemic inequality.

8. How is the caste system reflected in the glass-blowing industry of Firozabad?

Answer:

Caste perpetuates generational labor in Firozabad. Families believe it is their fate to work in glass furnaces. The system binds them not just economically but psychologically, normalizing suffering and silencing rebellion, thereby sustaining systemic exploitation across decades.

9. Why is Mukesh’s refusal to become a glass-blower a significant act of agency?

Answer:

Mukesh’s refusal challenges centuries of caste and poverty-imposed labor. Though modest, his dream disrupts fatalism. It reflects awareness, courage, and a belief in mobility—rare in his context. His agency gives the essay its most hopeful, revolutionary note.

10. What critique of government and social structures does the essay imply without stating directly?

Answer:

The essay exposes institutional apathy. Laws against child labor exist, yet children still suffer. Basic needs—education, healthcare, clean air—are absent. Jung’s quiet outrage lies in showing that structural failures are normalized, leaving the vulnerable to fend for themselves.

3 Questions (150-word answers)

1. Analyze how “Lost Spring” portrays poverty as both a cause and consequence of denied childhood.

Answer:

“Lost Spring” reveals how poverty erases the possibility of childhood. For Saheb, garbage collection is survival, not a game. For Mukesh, glass-blowing is not a tradition but bondage. These children inherit deprivation and are expected to accept it unquestioningly. Poverty forces them into labor at a tender age, stealing their time for play, imagination, and education. Worse, this early burden reinforces poverty in the next generation, as lack of schooling denies social mobility. Their lives become cycles of inherited struggle, sanctioned by tradition and ignored by authority. Anees Jung powerfully illustrates that poverty does not just take food or money—it takes time, identity, and agency. The essay humanizes statistical suffering by showing individual dreams crushed quietly under systemic failure, making childhood not a phase of growth but a rehearsal for endurance.

2. Discuss how symbolism enhances the emotional depth of “Lost Spring.”

Answer:

Anees Jung uses symbolism to layer emotional and thematic meaning. The title itself—“Lost Spring”—is a metaphor for childhood lost to labor. Garbage becomes a paradoxical symbol: for adults, it is economic survival; for children, a source of fleeting joy and possibility. The fence that separates Saheb from tennis players becomes a visual barrier between classes—between dreams and reality. Mukesh’s dusty clothes contrasted with his dream of working in a car garage highlight the visual conflict between aspiration and limitation. The tea stall and glass furnace represent routine imprisonment, while shoes—gifted or absent—serve as metaphors for incomplete access to privilege. These symbols make abstract suffering visible, giving a poetic but painful portrait of systemic injustice. Symbolism allows Jung to evoke empathy and compel readers to reflect on what remains unseen behind the statistics of child labor.

3. Evaluate the role of resilience in shaping the identities of children like Saheb and Mukesh.

Answer:

Resilience defines both Saheb and Mukesh, despite their adverse realities. Saheb faces the unpredictability of life in Seemapuri with curiosity. His smile when finding something in garbage, his cautious pride in owning shoes, and his acceptance of a tea stall job show emotional endurance amid harshness. Mukesh’s resilience is more deliberate. His dream to become a mechanic signals resistance against fatalism. He speaks not with grand defiance but quiet conviction—he wants to learn, even if it means walking to the garage far from home. Both boys reveal that resilience in poverty is not just survival; it is the persistence of desire, the will to believe in possibility. Their resilience is not glorified suffering but evidence of what remains human in dehumanizing conditions. It shapes their identity—not as victims, but as survivors and, in Mukesh’s case, as quiet rebeles.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————