Class 12 : History (English) – Lesson 8 Peasants, Zamindars and the State

EXPLANATION & SUMMARY

Explanation

🌿 The agrarian world under the Mughals: what, where, who

🔵 The sixteenth–seventeenth centuries saw a predominantly rural India in which farming supplied revenue to the state and grain to the towns. Fields, wells, village paths, tanks, groves and threshing floors formed a single working landscape. Most people were cultivators (raiyats/peasants), living in clustered hamlets linked to the nearest market and town.

🟢 Regional diversity mattered. The alluvial plains of the north and east produced rice and wheat; the black soils of the Deccan favoured cotton; the arid west relied on wells and hardy crops like millets; coastal belts grew rice, coconut and spices. Seasonality guided work: kharif (monsoon-sown) and rabi (winter-sown) were the basic cycles, with many peasants attempting two crops if water allowed.

🔴 Sources that help us reconstruct this world include the Ain-i Akbari of Abul Fazl (a detailed account of administration and revenue during Akbar), revenue manuals, farmans, village records kept by patwaris, and observations of travellers and merchants. Historians read these alongside inscriptions and the physical remains of canals, bunds and wells to balance praise, complaint and fact.

💧 Water, seed and labour: how agriculture worked

🔵 Irrigation was a constant concern. Persian wheels (saqiya), wells lined with stone, small bunds across seasonal streams, tanks and canals expanded cultivation beyond rainfall. In some regions rulers or local chiefs financed large tanks and canals; elsewhere village groups cooperated to desilt, repair and share water.

🟢 Ploughs were generally light, suited to local soils; bullocks drew them. Sowing, transplanting, weeding and harvesting required coordinated family and hired labour. Women’s work—transplanting seedlings, weeding, gleaning, winnowing, and managing fodder—was crucial though often under-recorded.

🔴 Crop choice balanced subsistence and sale. Staples included rice, wheat, barley and millets. High-value crops—sugarcane, cotton, indigo, oilseeds, tobacco (in the seventeenth century), fruits and garden vegetables—linked villages to distant markets. When water was secure, peasants mixed subsistence and commercial crops to spread risk and earn cash.

🧭 Types of peasants and village organisation

🔵 Not all peasants stood in the same position. Residents who held long-standing rights to plots were often called khud-kashta; those who migrated seasonally or recently to a village were pahi-kashta. The first group usually had stronger claims to irrigation turns and village commons; the second traded security for opportunity, helping expand cultivation in new tracts.

🟢 Villages managed themselves through a panchayat (assembly of elders) and officeholders. The headman (muqaddam/patel/mandal) coordinated tax payment and labour, the patwari kept land and crop registers, and the chaudhuri or qanungo supervised clusters of villages for the state. Panchayats mediated disputes, fixed fines and protected village resources.

🔴 Jati (caste) panchayats worked alongside village councils to settle marriage, inheritance and occupational matters. In many regions groups of hereditary service providers—blacksmiths, carpenters, barbers, potters, leather workers, drummers—received grain or shares for regular services, binding artisans and peasants in reciprocal arrangements.

🏰 Who were the zamindars?

🔵 Zamindars were holders of social and military authority over land and people in their localities. Some were old lineage chiefs; others had risen with conquests and royal appointments. They did not normally cultivate all the land themselves; instead they commanded armed followers, maintained order, collected revenue from cultivators in their areas and kept a portion as their right.

🟢 Their legitimacy rested on three strands: lineage and kinship ties with villagers; ritual status through temple, mosque or shrine patronage; and recognition by the state through sanads. Zamindars offered protection during scarcity, sponsored embankments and wells, settled new migrants and sometimes advanced seed or cash. In return they expected obedience, labour dues and a respectful share of produce.

🔴 The line between zamindar and peasant could blur. A prosperous peasant household might expand into share-cropping management and local leadership; a small zamindar might farm part of his lands directly. But as a group, zamindars formed the hinge between village society and the imperial system.

🧮 Land revenue: principles, practices and people

🔵 The Mughal state’s financial backbone was land revenue. Two terms recur in records: jama (assessed demand) and hasil (actual realisation). To make jama realistic, officers measured fields, classified soils and determined average yields and prices. In core regions Akbar’s regime stabilised revenue with the zabt system—cash assessment based on ten-year averages of prices and produce (the dahsala method).

🟢 Where measurement was difficult or fluctuation high, the state used crop-sharing methods (batai/ghalla-bakshi) or a valuation called nasaq. In crop-sharing the state received a fixed fraction of the actual harvest; the share was often collected at the threshing floor. The preference for cash assessment increased as markets expanded and coin circulation deepened.

🔴 Revenue staff included the diwan (chief revenue officer), amil/amil-guzar (district collector), qanungo (record specialist) and patwari (village record-keeper). Standardised measurement with bamboo rods (jarib), lists of local rates (dastur-ul-amal) and season-wise schedules disciplined collection. But negotiations were constant: drought rebates, remissions for flood, and disputes over assessment kept the system flexible.

🪙 Money, markets and the commercialisation of agriculture

🔵 From the late sixteenth century a surge of silver through global trade strengthened the rupee and eased cash payments. Peasants sold part of their produce to meet revenue demands; merchants and moneylenders advanced cash before harvest, taking repayment in grain or coin. Hundis (bills of exchange) linked distant markets; grain moved from surplus zones to deficit towns.

🟢 Weekly haats and larger mandis knit the countryside to urban centres. Cotton from the Deccan, indigo from north India and sugar from river basins fed handicrafts and overseas trade. Prices and wages fluctuated with harvests, warfare and coin supply; careful peasants diversified crops or entered sharecropping to hedge risk.

🔴 Monetisation did not mean the end of customary exchange. Service groups still received payments in kind; temple and mosque kitchens distributed food; and village commons supported grazing, fuel-gathering and thatching—vital buffers in lean times.

🛡️ Mansabdars, jagirs and the flow of revenue upwards

🔵 The empire paid its officers (mansabdars) not mainly in cash salaries but by assigning them jagirs—revenue rights over specified areas. Jagirdars were responsible for collecting the assessed revenue and remitting a share to the imperial treasury after paying their own contingents. Transfers of jagirs were frequent to prevent local entrenchment.

🟢 This meant the village rupee climbed a ladder: peasant to amil, to jagirdar, to imperial centre. Any break—excessive assessment, crop failure, coercion, illegal cesses, or corruption—stressed the system. Over-assignment and shrinking unencumbered lands in the seventeenth century produced friction labelled by historians as the “jagirdari crisis”, especially under Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb.

🔴 In practice, success depended on negotiated cooperation among peasants, zamindars, jagirdars and officials. Where cooperation held, cultivation expanded; where it failed, revenue fell and conflicts sharpened.

⚖️ Everyday justice and conflict in the countryside

🔵 Panchayats tried to resolve disputes over fields, water turns, wages, loans and inheritance. Fines were levied, sometimes expended on village wells or paths. Jati panchayats enforced norms in marriage and occupation, issuing penalties or temporary outcasting.

🟢 When pressure rose—through high assessment, forced labour, or disrespect for local rights—tensions flared. Some conflicts stayed local; others turned into open resistance led by zamindars or armed peasantries. Seventeenth-century uprisings of Jats and Satnamis in the north-west, and resistance in forest fringes, illustrate how agrarian discontent could acquire military form.

🔴 The state alternated between negotiation and suppression. Remission, recognition of rights, or reassignment could calm a district; harsh campaigns could equally be ordered where authority was challenged.

🌳 Forests, frontiers and pastoral worlds

🔵 Forest belts and uplands supplied timber, honey, wax, lac and medicinal plants; they also housed communities practicing shifting cultivation and pastoralism. The state sought to settle some groups, levy tribute on others and open tracts for plough cultivation.

🟢 Chiefs in forested or hilly zones often acted as zamindars—guarding passes, mediating with mobile groups, and supplying soldiers and pack animals. As ploughlands expanded, boundaries between settled and shifting cultivators shifted too, creating negotiation and sometimes conflict over access to resources.

🔴 Pastoral herds—cattle, buffalo, sheep and goats—were integral to agriculture for traction, manure and dairy. Seasonal migration followed grazing and water. Revenue demand sometimes took the form of grazing taxes or supply obligations.

🧵 Peasants, artisans and the rural craft economy

🔵 Farming households also spun, wove, pressed oil and made jaggery—activities that blurred the line between agriculture and craft. In some regions hereditary service groups (e.g., balutedars in the Deccan) were paid in shares of the harvest for the year’s work.

🟢 Craft and field intersected at every step: wooden ploughs required carpenters; iron tips needed smiths; wells needed rope-makers and masons; temple and household rituals sustained potters, florists and musicians. These chains tied livelihoods to both harvest and festival.

🔴 Women’s labour underpinned many of these tasks—spinning, husking, fuel and water collection, small animal care—besides fieldwork. Legal customs about inheritance varied across regions and jatis, shaping how women accessed land and resources.

📚 Reading the Ain-i Akbari and other sources carefully

🔵 Abul Fazl’s Ain-i Akbari lists sarkars and parganas, schedules of prices, wages and crop yields, and procedures of measurement. It explains categories of land like polaj (cultivated annually), parauti (left fallow for recovery), chachar and banjar (long fallow or waste to be reclaimed), showing how officials planned to improve cultivation.

🟢 Yet the Ain is a model of what ought to be as much as what was. Local practice could depart from prescriptions. That is why historians compare the Ain to later revenue reports, village records and evidence preserved on the ground—canal gradients, tank beds, bunds, and settlement patterns—before drawing conclusions.

🔴 Travellers illuminate everyday life: they noted bustling markets, processions, sowing rituals, thriving textile towns and also famines, high prices or extortions. Their vantage points were limited but their details, when cross-checked, help humanise the statistical picture.

🔁 Change across the seventeenth century

🔵 Expansion continued in many regions through new clearings and irrigation, but pressures rose: heavy military commitments, competition among elites for jagirs, and fluctuations in silver inflow affected prices and assessments.

🟢 Some zamindar houses consolidated power, while others were displaced by imperial appointments. In certain zones, groups like the Marathas built on agrarian revenues to create new political formations. The countryside remained dynamic—never static or uniform—even under a strong empire.

🔴 What endured was the mutual dependence of crown, zamindar and peasant. Each needed the other for grain, order and legitimacy; each bargained for a workable share.

🧩 Key ideas to carry forward

🔵 Agrarian society was not simply “peasants paying tax.” It was a layered system of rights, obligations and negotiations, embedded in water control and local institutions.

🟢 The Mughal fiscal order sought standardisation but allowed regional variation; cash demands pushed commercialisation, yet customary exchange and village solidarity persisted.

🔴 Zamindars were not mere tax farmers; they were social leaders with ritual and military roles, indispensable yet sometimes oppositional.

🟡 The strength and stress of the empire alike coursed through this rural world. When harvests were good and cooperation held, the empire prospered; when monsoon failed or mediation broke, conflict followed.

Summary (~300 words)

🔵 India under the Mughals was overwhelmingly agrarian. Fields, tanks, wells and market paths formed a working landscape that varied by region and season. Peasants (khud-kashta and pahi-kashta) organised labour within families and through hired hands; women’s contributions were central. Irrigation by wells, Persian wheels, tanks and canals allowed two crops in many places. Staples like rice and wheat coexisted with high-value crops such as cotton, sugarcane and indigo, encouraging links to markets.

🟢 Villages managed themselves through panchayats and officeholders (muqaddam/patel, patwari), while jati panchayats governed social norms. Zamindars stood between state and village as military-fiscal leaders: they protected, settled people, sponsored works and collected revenue, retaining a recognised share.

🟡 Mughal revenue depended on jama (assessment) and hasil (realisation). In core regions Akbar’s zabt/dahsala fixed cash demand using ten-year price and yield averages; elsewhere crop-sharing (batai) or nasaq operated. Standardised measurement, records and schedules disciplined collection, although remission and negotiation were common in bad years.

🔴 Monetisation deepened with abundant silver; peasants sold produce to pay revenue, using credit from merchants and moneylenders. Hundis linked markets; weekly haats and larger mandis moved grain, cotton, indigo and sugar. Customary payments in kind and village commons continued as safety nets.

🟢 Mansabdars received jagirs (revenue assignments) to maintain contingents, tying village rupees to imperial armies. Frequent transfers tried to prevent entrenchment, yet over-assignment and pressure in the seventeenth century generated tensions sometimes termed a jagirdari crisis.

🟡 Panchayats settled routine disputes; when pressure grew, conflicts escalated—some turning into zamindar-led resistance. Forest and pastoral zones supplied resources and recruits while negotiating tribute and settlement. Throughout, the agrarian order remained a negotiated system where water control, local institutions, zamindari leadership and imperial revenue policy together shaped rural life.

📝 Quick Recap

🟢 Peasants, water and labour formed the base; irrigation plus seasonal rhythms organised work and crops.

🔵 Village councils and jati panchayats managed local order; zamindars mediated between villagers and the state.

🟡 Akbar’s zabt/dahsala standardised cash assessment; elsewhere crop-sharing continued; jama vs hasil tracked demand and collection.

🔴 Monetisation grew with silver inflows, markets and credit (hundi), but customary exchanges in kind persisted.

🟣 Mansabdars drew jagir revenue to fund troops; transfers tried to curb local entrenchment, leading at times to jagirdari tensions.

🟠 Conflicts arose when assessment, coercion or rights clashed; negotiation, remission and local institutions kept the system functioning.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

QUESTIONS FROM TEXTBOOK

🔵 Question 1: What are the problems in using the Ain as a source for reconstructing agrarian history? How do historians deal with this situation?

🟢 Answer (≈130–145 words):

🟡 • The Ain is a courtly, prescriptive compilation; it often states how things ought to work, not how they always worked in villages.

🔴 • Data are aggregated at pargana/sarkar levels; regional gaps, uneven coverage and possible scribal/translation errors limit precision.

🔵 • Price and yield lists reflect core regions and crowned years; crises, local fluctuations and informal cesses may be muted.

🟣 • Abul Fazl writes to glorify Akbar; administrative ideals and political rhetoric colour descriptions of measurement and justice.

🟢 How historians respond:

✨ • Triangulate with farmans, revenue registers (patwari/qanungo), inscriptional grants and later district records.

💠 • Correlate with archaeology: canals, tank-bunds, threshing floors, settlement layouts.

🧭 • Cross-check travellers’ accounts, court chronicles and climate/price series.

📌 • Read internal consistencies (jama–hasil gaps, remission notes).

✔️ Result: a balanced picture emerges by combining the Ain’s model with diverse, ground-level evidence.

🔵 Question 2: To what extent is it possible to characterise agricultural production in the sixteenth-seventeenth centuries as subsistence agriculture? Give reasons for your answer.

🟢 Answer (≈120–145 words):

🟡 • Subsistence elements were strong: most households prioritised staples (rice, wheat, millets); labour, tools and water were limited; risk-averse strategies (mixed crops, fallows) guarded against failure.

🔴 • Payments in kind to service groups and village commons for fodder/fuel kept non-market exchanges alive.

🔵 Yet it was not merely subsistence:

✨ • Cash revenue under zabt and nasaq pushed peasant sales; silver inflows widened monetisation.

💠 • Commercial crops—cotton, indigo, sugarcane, oilseeds, later tobacco—linked villages to mandis and long-distance trade.

🧭 • Double-cropping where irrigation allowed, orchard/garden cultivation near tanks, and advances from sahukars encouraged market production.

📌 • Grain moved from surplus to deficit zones via merchants and hundis.

✔️ Conclusion: agriculture combined subsistence security with significant commercialisation, varying by region, water and market access.

🔵 Question 3: Describe the role played by women in agricultural production.

🟢 Answer (≈110–135 words):

🟡 • Field tasks: transplanting paddy, weeding, harvesting, gleaning; guarding crops and birds at ripening time.

🔴 • Post-harvest: threshing, winnowing, drying, storing grain; cleaning seed, maintaining bins and smoke-curing.

🔵 • Livestock and inputs: collecting fodder, dung and leaf-litter; stall-feeding cattle/buffalo; dairying and small poultry/goat care.

🟣 • Household processing: grinding, husking, oil-pressing/jaggery in seasons; spinning yarn for family textiles.

🟢 • Water and fuel work sustained cultivation cycles (well-turns, fetching, bund maintenance).

✨ • Ritual and social labour—offerings, festival cooking, feeding travellers—bound households to temple/mosque kitchens and village reciprocity.

📌 • Records understate women’s labour because wages/contracts named male heads, but production and reproduction of farm life relied heavily on women’s continuous, skilled work.

🔵 Question 4: Discuss, with examples, the significance of monetary transactions during the period under consideration.

🟢 Answer (≈120–145 words):

🟡 • Cash revenue (zabt/dahsala) required peasants to sell part of produce; silver rupees circulating from global trade facilitated payments.

🔴 • Credit expanded: sahukars advanced seed/cash against harvest; hundis moved money securely between towns and mandis.

🔵 • Wages and purchases increasingly used coin in towns and many villages (tools, salt, iron tips, cloth), knitting producers to markets.

🟣 • Crop choices responded to cash: cotton, indigo, sugarcane, oilseeds and garden produce fetched money for revenue and rents.

🧭 • Jagirdars and mansabdars drew income from assigned revenues to pay contingents; transfers of jagirs tracked fiscal flows.

📌 • Even where kind-payments persisted for service groups, coin eased large transactions, taxes, litigation fees and pilgrimage.

✔️ Overall, monetisation integrated countryside and towns, spread risk via credit, and underwrote both imperial finance and rural change.

🔵 Question 5: Examine the evidence that suggests that land revenue was important for the Mughal fiscal system.

🟢 Answer (≈125–145 words):

🟡 • Administrative design centred on revenue: diwans, amils, qanungos and patwaris recorded fields, soils, yields and remissions; jama (assessment) versus hasil (realisation) was tracked annually.

🔴 • Akbar’s revenue reforms (measurement, dahsala price-averages, schedules) aimed to stabilise imperial income and officer payments.

🔵 • Jagirdari system assigned revenue areas to mansabdars for salary; frequent transfers and audits show dependence on steady land income.

🟣 • Court chronicles and the Ain emphasise land-based receipts as the primary source for military and ceremonial expenditure.

🧭 • Rebellions, shortages and “jagirdari crisis” debates are framed around competition for productive assignments, underscoring fiscal centrality of land.

📌 • Inscriptions and village records note temple/mosque endowments funded from land dues, reflecting the reach of agrarian revenue.

✔️ Together, administrative machinery, officer remuneration and political tensions all point to land revenue as the mainstay of Mughal finance.

🔵 Question 6: To what extent do you think caste was a factor in influencing social and economic relations in agrarian society?

🟢 Answer (≈250–300 words):

🟡 • Caste organised everyday production and exchange. Hereditary service groups (smiths, carpenters, barbers, potters, leather-workers, drummers) received grain shares or plots for annual services, fixing obligations between cultivators and artisans.

🔴 • Access to land, water-turns and village commons was graded; dominant cultivating castes or lineages often controlled headmanship (muqaddam/patel) and office networks with patwaris/qanungos, shaping assessment and dispute outcomes.

🔵 • Commensality and ritual status rules affected wage meals, hiring and neighbourhood layout; jati panchayats enforced marriage and inheritance norms, levying fines or temporary outcasting.

🟣 • Women’s work cut across ranks, yet property and mobility followed caste-specific customs; widows’ rights or remarriage varied, altering household labour and control of plots.

🧭 • Still, caste was not an immovable wall. Migration (pahi-kashta), forest-edge clearings, military recruitment and market opportunities produced slippages. Prosperous peasants could acquire leadership; impoverished lineages lost ground.

✨ • The state’s fiscal routines (measurement, remission) and supra-local institutions (shrines, mandis) overlaid caste grids, sometimes moderating local dominance.

📌 • Conflicts—over taxes, water or honour—often took caste shape, yet settlements commonly relied on compromise in panchayats or imperial arbitration.

✔️ Assessment: caste strongly structured labour, authority and everyday hierarchy in agrarian society, but its effects were mediated by migration, markets, state revenue practice and environmental change. It was a powerful framework, not the only determinant.

🔵 Question 7: How were the lives of forest dwellers transformed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries?

🟢 Answer (≈250–300 words):

🟡 • Expansion of cultivation pressed into forest belts. Chiefs received recognition as zamindars if they settled people, guarded passes and supplied soldiers; tribute replaced some customary dues.

🔴 • Shifting cultivators faced regulation: periodic burning and fallow cycles were curtailed where plough agriculture advanced; some groups were encouraged to adopt permanent fields and pay assessed revenue.

🔵 • Demand for forest produce—timber, honey, wax, lac, medicinal plants—rose with urban growth and shipbuilding; merchants interposed brokers and advances, drawing forest households into credit and price systems.

🟣 • Labour needs of canals, bunds, roads and military campaigns recruited forest men as woodcutters, boatmen and soldiers; elephants and pack animals came from these zones.

🧭 • Sacred geographies spread: shrines, fairs and Sufi/monastic hospices at edges of clearings tied communities to wider ritual economies, sometimes altering dietary and marriage norms.

✨ • Not all change was enrichment. Encroachment reduced hunting grounds and commons; new taxes, debt and punitive policing generated flight or resistance. Some leaders negotiated favourable terms; others joined rebellions or shifted allegiance between empire and regional powers.

📌 • In several regions people moved between statuses—hunter-gatherer, shifting cultivator, peasant foot-soldier—across a lifetime, reflecting fluidity at the frontier.

✔️ Net effect: forest dwellers became more entangled with markets, revenue and politics—some prospered as intermediaries, many faced loss of autonomy and seasonal insecurity.

🔵 Question 8: Examine the role played by zamindars in Mughal India.

🟢 Answer (≈250–300 words):

🟡 • Zamindars were local military-fiscal leaders who claimed customary rights over land and people. They collected revenue from raiyats, retained a recognised share and remitted the rest through officials to jagirdars/imperial treasury.

🔴 • Authority rested on lineage ties, control of retainers, and ritual prestige through temple/mosque patronage; they mediated disputes, protected markets and sponsored wells, bunds and shrines.

🔵 • In settlement and expansion, zamindars invited migrants (pahi-kashta), advanced seed/oxen, cleared scrub and safeguarded new hamlets. Their seals and genealogies legitimised boundaries and water-turns.

🟣 • As brokers with the state, they organised labour for roads, canal repairs and muster when campaigns were called; in return they sought honours, robes, titles and confirmation of rights.

🧭 • Tensions were intrinsic: excessive assessment, encroachment on privileges or jagirdar abuse could push zamindars into litigation or armed resistance; conversely, imperial recognition could elevate them above rivals.

✨ • Economically, their endowments supported religious institutions and fairs; their spending sustained local crafts and trade. Some diversified into transport animals, indigo/sugar ventures or moneylending.

📌 • The seventeenth century saw sharper competition for revenue spheres; certain houses rose to regional power while others were displaced.

✔️ Overall, zamindars were not mere tax-collectors: they were central to agrarian governance, settlement, security and culture—indispensable collaborators and potential challengers to imperial authority.

🔵 Question 9: Discuss the ways in which panchayats and village headmen regulated rural society.

🟢 Answer (≈250–300 words):

🟡 • The panchayat—an assembly of elders—adjudicated local disputes over fields, water-shares, wages, loans, boundary stones and stray cattle. Fines were levied and often spent on wells, paths or festival expenses, turning punishment into communal benefit.

🔴 • The headman (muqaddam/patel) coordinated revenue payment and labour dues, mobilised watchmen, and represented the village to amils; the patwari kept detailed registers of holdings, crops, remissions and transfers.

🔵 • Jati panchayats worked alongside the village council on marriage, inheritance and occupational rules; they could censure, fine or temporarily outcaste offenders, later readmitting them on prescribed rites.

🟣 • Commons and resources were regulated collectively: grazing turns, fuel collection, access to tanks/wells and desilting schedules were fixed to balance households and seasons.

🧭 • In scarcity years, councils negotiated remissions, organised grain loans and supervised price controls at fairs; they also guarded gates and watch-paths, limiting theft and protecting harvests.

✨ • Panchayats recorded agreements in writing or witnessed oaths at shrines, giving decisions social and moral force even without permanent police.

📌 • Power was unequal—dominant lineages could influence verdicts—but appeal to higher officials or to religious authorities sometimes corrected bias.

✔️ Thus, village headmen and panchayats provided everyday governance—keeping peace, managing resources, mediating with the state and maintaining a workable social order in the countryside.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

OTHER IMPORTANT QUESTIONS FOR EXAMS

🔵 Question 1: who authored the ain-i akbari

A. abul fazl

B. badauni

C. bernier

D. ferishta

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 2: in revenue records, jama refers to

A. actual cash received

B. assessed demand

C. remission

D. unpaid balance

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 3: the dahsala/zabt method under akbar used

A. military quotas

B. ten-year average prices/yields for cash assessment

C. crop-sharing at threshing floors

D. village auctions

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 4: jarib in mughal revenue practice was a

A. ploughshare

B. bamboo measuring rod

C. water-wheel bucket

D. coin scale

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 5: polaj land meant

A. long fallow waste

B. land cleared that year only

C. land cultivated annually without fallow

D. forest land under tribute

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 6: parauti land was

A. under permanent pasture

B. left temporarily fallow to recover

C. submerged tank-bed

D. newly reclaimed long fallow

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 7: batai/ghalla-bakhshi denotes

A. lump-sum cash rent

B. forced labour

C. crop-share between cultivator and state

D. pasture tax

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 8: khud-kashta peasants were

A. non-resident migrants

B. resident cultivators of long standing

C. pastoral nomads

D. temple servants

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 9: zamindar in mughal india best refers to

A. imperial treasurer

B. local military-social leader with revenue rights

C. hired village watchman

D. travelling grain merchant

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 10: saqiya was used for

A. coin testing

B. lifting water by a persian wheel

C. measuring fields

D. pounding grain

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 11: kharif crops are sown mainly

A. in winter after the retreating monsoon

B. in spring only

C. with the onset of the southwest monsoon

D. in the hot dry months

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 12: the provincial diwan was primarily the

A. judicial head

B. chief revenue officer

C. army paymaster

D. road superintendent

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 13: patwari was responsible for

A. minting coins

B. village land and crop registers

C. policing highways

D. running weekly markets

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 14: qanungo functioned as

A. irrigation engineer

B. record specialist at pargana/district level

C. temple trustee

D. crop-insurance broker

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 15: jagir was

A. cash stipend to soldiers

B. hereditary kingdom

C. revenue assignment in lieu of salary to mansabdars

D. royal hunting ground

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 16: hundi in the period meant

A. land mortgage deed

B. bill of exchange/credit instrument

C. tithe on orchards

D. river ferry ticket

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 17: hereditary village service groups (smiths, carpenters, barbers, potters) were typically paid through

A. monthly cash wages only

B. imperial jagirs

C. shares of the harvest/in-kind dues

D. European company contracts

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 18 (match-the-columns): match the term (column i) with the meaning (column ii).

column i: (i) hasil (ii) chachar (iii) banjar (iv) muqaddam

column ii: (p) village headman (q) actual realisation (r) fallow of 3–4 years/newly reclaimed (s) long-fallow/waste

A. (i–q), (ii–r), (iii–s), (iv–p)

B. (i–s), (ii–q), (iii–p), (iv–r)

C. (i–p), (ii–s), (iii–r), (iv–q)

D. (i–r), (ii–p), (iii–q), (iv–s)

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 19 (assertion–reason):

assertion (a): monetary transactions expanded in the sixteenth–seventeenth centuries.

reason (r): increased inflow of silver through global trade strengthened coin supply.

A. both a and r are true, and r explains a

B. both a and r are true, but r does not explain a

C. a is true but r is false

D. a is false but r is true

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 20 (assertion–reason):

assertion (a): zamindars were mere revenue farmers without social authority.

reason (r): they lacked ritual/military roles in local society.

A. both a and r are true, and r explains a

B. both a and r are true, but r does not explain a

C. a is true but r is false

D. a is false but r is true

🟢 Answer: D

🔵 Question 21 (picture/id — text alternative): identify the term for “a device with pots fixed to a wheel turned by oxen to raise well-water for irrigation.”

A. jarib

B. saqiya

C. qanat

D. chakla

🟢 Answer: B

— section b: short answer i (60–80 words each) —

🔵 Question 22: explain jama and hasil and why the distinction mattered.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • jama = assessed demand set after measurement, soil class and price/yield averages.

🔴 • hasil = actual realisation collected in the year.

🔵 • the gap showed success or stress of a district: droughts, remissions, resistance or corruption.

🟣 • administrators adjusted demand, granted rebate or changed methods (cash vs batai) using this signal, while jagir transfers and audits relied on jama–hasil comparisons.

🔵 Question 23: describe khud-kashta and pahi-kashta peasants and their roles in expansion.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • khud-kashta were resident peasants with established rights to plots, irrigation turns and commons; they anchored village stability.

🔴 • pahi-kashta were migrants/seasonal settlers who cleared new tracts, accepted flexible terms and helped push cultivation outward.

🔵 • together they balanced security and mobility: one preserved routines and records; the other supplied labour and risk-taking needed for reclamation and revenue growth.

🔵 Question 24A (attempt any one): distinguish cash assessment (zabt/dahsala) from crop-share (batai) with one context each.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • zabt/dahsala fixed cash demand from ten-year price/yield averages; suited measured, stable core regions with good markets.

🔴 • batai took a fixed fraction of the actual harvest at the threshing floor; used where measurement was hard or yields fluctuated, sharing risk between state and peasant.

🔵 Question 24B (attempt any one): list three routine functions of a village panchayat/headman in regulating rural life.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • mediated disputes over fields, water-turns, wages and boundaries; levied fines.

🔴 • coordinated tax payment, watch and road maintenance; kept crop/holding registers through the patwari.

🔵 • managed commons (grazing, desilting schedules), organised relief/loans in scarcity and represented the village to revenue officials.

🔵 Question 25: show two ways zamindars aided settlement and one tension that could arise.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • invited migrants, advanced seed/oxen and protected hamlets; sponsored wells/bunds and shrines to anchor communities.

🔴 • mediated with officials, mustered retainers for security and campaigns.

🔵 • tension: over-assessment or encroachment on rights could trigger litigation or armed resistance, straining centre–local cooperation.

🔵 Question 26A (attempt any one): list three features of monetary transactions that linked villages to markets (60–80 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • sahukars advanced seed and cash; repayment came in coin or grain after harvest, spreading risk.

🔴 • hundis (bills of exchange) moved money safely between mandis; merchants settled long-distance purchases without hauling cash.

🔵 • cash revenue under zabt pushed peasants to sell part of produce; high-value crops (cotton, indigo, sugarcane, oilseeds) generated rupees for taxes, rents and tools, tying raiyats to weekly haats and urban demand.

🔵 Question 26B (attempt any one): give three points showing commercialisation did not end customary exchange (60–80 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • hereditary service groups (smiths, carpenters, barbers, potters) still received in-kind shares from harvests.

🔴 • temple/mosque kitchens, fairs and charity fed travellers and the poor with grain, not coin.

🔵 • village commons (grazing, fuelwood, thatch) and labour exchange during bund repairs persisted, cushioning households despite growing monetisation.

🔵 Question 27: explain two ways caste shaped agrarian relations and one limit to its power (60–80 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • dominant cultivating jatis often held headmanship and better water turns, influencing assessments and dispute outcomes.

🔴 • commensality and ritual status rules affected hiring, wage meals and neighbourhood layout.

🔵 • limit: migration (pahi-kashta), state revenue routines, markets and military recruitment opened slippages—new settlers gained plots and some poorer lineages rose through service or trade.

🔵 Question 28A (attempt any one): to what extent did caste influence social and economic relations in agrarian society (300–350 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 caste operated as a daily organiser of production, distribution and honour. In most villages hereditary service groups—blacksmiths, carpenters, barbers, potters, leather workers, drummers—held reciprocal ties with cultivators, receiving annual grain shares or plots for fixed services. These ties embedded labour and skill within the harvest calendar, so that sowing, repairs and rituals found workers on time. Dominant cultivating jatis typically occupied headmanship and nodal offices, controlling access to irrigation turns, village commons and the panchayat’s sanctions; they set the tone of fines, wages in kind and marriage rules that affected land, labour and credit.

🔴 Commensality norms shaped everyday economics: who ate whose food, who shared a water source, and who fetched wages cooked or raw. Spatial segregation of hamlets mirrored status, and jati panchayats enforced inheritance and occupational boundaries, imposing penalties or temporary outcasting for breaches. Women’s work cut across ranks—transplanting, weeding, threshing, spinning—but inheritance customs within jatis set how far women could command land or cash, influencing household resilience.

🔵 Yet caste was not absolute. Migration to new clearings (pahi-kashta), entry into military retinues or artisanal niches, and expansion of markets under coin circulation enabled movement. The imperial revenue apparatus introduced external criteria—measurement, remission schedules, audits—that sometimes moderated local dominance; shrine networks and mandis also created supra-local affiliations. Conflicts often took caste form—disputes over water, boundary stones, or insult—but were settled through negotiated fines, recorded agreements, or appeals to officials.

🟢 Overall, caste provided the grammar of rural hierarchy, embedding authority and reciprocity in everyday life; but monsoon variability, market incentives, migration and state routines continually bent the rules, producing a landscape of constraint mixed with opportunity.

🔵 Question 28B (attempt any one): how were the lives of forest dwellers transformed in the sixteenth–seventeenth centuries (300–350 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 Agrarian expansion pressed into forest belts as rulers and zamindars sought new revenue. Chiefs along uplands and passes received recognition as zamindars when they guarded routes, levied tribute and settled cultivators. Shifting cultivators met regulation: burning cycles and long fallows were restricted near new fields; some groups were encouraged or coerced to adopt plough agriculture, water turns and tax schedules.

🔴 Urban growth raised demand for timber, charcoal, resin, lac, honey and medicinal plants; merchants offered advances and set prices, drawing forest households into credit systems and litigation. Military and public works needed woodcutters, boatmen, porters and soldiers; elephants and pack animals came from these regions, creating new incomes but also obligations.

🔵 Sacred geographies moved outward: shrines and fairs on edges of clearings tied participants to broader ritual economies; Sufi hospices and mathas mediated disputes and offered charity. Such links sometimes softened boundaries of diet, dress and marriage, but also deepened dependence on grain markets when foraging grounds shrank.

🟣 Not all outcomes were enrichment. Encroachment reduced wildlife and commons, while new taxes and debt heightened seasonal insecurity. Leaders bargained for favourable terms—reduced tribute, rights over salt or timber—yet others joined resistance when officials or rival zamindars imposed burdens. Movement across statuses was common: a person might be hunter, shifting cultivator, porter and peasant-soldier at different life stages.

🟢 Net effect: deeper entanglement with revenue, markets and politics. Some groups prospered as intermediaries; many lost autonomy, illustrating how imperial expansion remade both forests and fields.

🔵 Question 29A (attempt any one): examine the role played by zamindars in Mughal India (300–350 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 Zamindars stood at the hinge of empire and village. Their authority rested on lineage prestige, followers and ritual patronage; they collected revenue within their domains, kept a recognised share and remitted the balance through officials to jagirdars and the centre. As brokers, they organised labour for bund repairs, canal desilting and road security, and they mustered retainers for campaigns on summons.

🔴 In settlement, they invited migrants (pahi-kashta), advanced seed or oxen, cleared scrub and marked boundary stones, thereby widening the cultivable base. Endowments for shrines, fairs and feeding houses stabilised communities and advertised legitimacy. Market peace and toll collection under their watch encouraged merchants to frequent weekly haats and larger mandis.

🔵 Yet the position bred tension. Competition for productive tracts, over-assessment by jagirdars, or encroachment on customary dues could spark litigation or armed resistance. Conversely, imperial robes of honour, titles and confirmation of rights bound powerful houses to the throne, elevating them over rivals. In the seventeenth century, as jagirs grew tighter and military expenses rose, conflicts sharpened in some regions; elsewhere, zamindar lineages leveraged revenue into regional power.

🟣 Economically, their spending sustained crafts—smiths for tools, carpenters for ploughs, weavers for retainers’ cloth. Ritual redistribution (feasts, alms) and market linking made them engines of local circulation.

🟢 In sum, zamindars were not mere tax-collectors: they were social leaders, patrons and military brokers whose cooperation underwrote imperial stability, and whose defection exposed its limits.

🔵 Question 29B (attempt any one): discuss the ways panchayats and village headmen regulated rural society (300–350 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 The panchayat, an assembly of elders, provided everyday governance. It adjudicated disputes over field boundaries, irrigation turns, wages, loans and inheritance. Fines financed wells, path repairs or festival expenses, converting punishment into communal goods. Written undertakings or oaths at shrines endowed decisions with moral force.

🔴 The headman (muqaddam/patel) coordinated tax payment and labour dues, mobilised watchmen, and represented the village to the amil; the patwari kept registers of holdings, crops and remissions. Together they scheduled desilting of tanks, repair of bunds and guarding of harvested fields, allocating labour by household capacity.

🔵 Jati panchayats worked alongside the village council on marriage rules, inheritance customs and occupational norms; they could censure, fine or temporarily outcaste offenders, later readmitting them through prescribed rites. These institutions managed commensality and neighbourhood order, ensuring predictable cooperation across busy seasons.

🟣 In scarcity or price spikes, councils negotiated remissions, arranged grain loans, and moderated market malpractice. They supervised tolls on fair days and set rules for visiting traders. Appeals upward—to pargana officials or religious authorities—existed, curbing blatant bias.

🟢 Power was unequal: dominant lineages often steered verdicts. But the panchayat’s success lay in keeping small conflicts out of costly litigation and in preserving workable relations among peasants, artisans and service groups. It thus functioned as the countryside’s everyday court, labour board and resource manager.

🔵 Question 30A (attempt any one): assess the strengths and limits of the Ain-i Akbari for agrarian history and how historians use it (300–350 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 The Ain offers a rare, systematised view of administration: lists of sarkars and parganas, schedules of prices and wages, crop yields, land categories (polaj, parauti, chachar, banjar), procedures of measurement, and the dahsala method for cash assessment. It outlines offices (diwan, amil, qanungo, patwari) and their paperwork, enabling reconstruction of fiscal machinery and vocabulary.

🔴 Limits arise from purpose and perspective. It is a courtly, prescriptive compilation that often states how the system ought to function rather than reporting village realities. Data are aggregated, with regional gaps and biases toward core provinces; crises and informal cesses may be underreported. Rhetorical praise of imperial justice colours depictions of remission and discipline.

🔵 Historians therefore triangulate. They compare the Ain’s rates with later district records, farmans and village papers; read jama–hasil gaps for stress; and correlate terrain evidence—canal lines, tank bunds, threshing floors—with the text’s claims. Travelogues by Persian and European visitors provide vignettes of markets, processions and famines; archaeology and climate proxies (tree-rings, flood layers) test price and yield patterns.

🟣 Measurement technology (jarib), standard cesses and office chains can be tracked across regions; where practice deviates, scholars ask why—soil, water, population or politics. The result is a calibrated narrative: the Ain supplies the model and language of governance, while comparison with ground-level records and material remains recovers variation and change.

🟢 Thus, used critically and comparatively, the Ain is indispensable—neither a mirror of reality nor mere rhetoric, but a scaffold on which reliable agrarian histories can be built.

🔵 Question 30B (attempt any one): explain the growth of monetary transactions and their effects on agriculture and the state (300–350 words)

🟢 Answer:

🟡 A surge of silver through global trade from the late sixteenth century strengthened coin supply. Akbar’s cash assessments (zabt/dahsala) locked revenue into rupees, pushing peasants to sell produce. Merchants and sahukars advanced cash and seed, taking repayment in grain or coin; hundis linked distant markets, letting money travel without risk.

🔴 Agriculture responded: areas with reliable water increased double-cropping; villages mixed staples with cash earners—cotton, indigo, sugarcane, oilseeds, garden produce. Tools, iron plough-tips and textiles were increasingly bought with coin; wages in towns and many villages shifted partly to cash. Grain moved from surplus tracts to deficit towns along enhanced mandi networks.

🔵 For the state, monetisation improved fiscal predictability and simplified transfers to jagirdars and the army. Jagir assignments converted coin flows into military pay, while frequent jagir transfers prevented local entrenchment. Yet tight assignments and price fluctuations in the seventeenth century created stress—labelled the jagirdari “crisis”—when officers competed for productive tracts and peasants faced heavier exactions.

🟣 Monetisation never erased customary exchange: service groups still received in-kind dues; charity kitchens and festival distributions redistributed grain; commons buffered poor households. Credit could ease lean seasons but also trap families in debt if harvests failed.

🟢 Net effect: money thickened links between field, market and state, enabling imperial scale and rural change, while leaving a mixed economy where coin and custom coexisted.

🔵 Question 31 — source/case (1+1+2)

“the amil read the qanungo’s register; at the threshing floor the share was measured. in a dry year the village asked for remission; the hasil fell short of the jama.”

(a) name two terms that track demand and realisation.

(b) identify the place where crop-share could be collected.

(c) explain one way such records helped governance.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 (a) jama (assessed demand) and hasil (actual realisation).

🔴 (b) at the threshing floor during batai.

🔵 (c) comparing jama with hasil signalled stress or success, guiding remissions, audits and method changes (cash vs share), and informing jagir transfers.

🔵 Question 32 — source/case (1+1+2)

“oxen turned the wheel; pots lifted well-water into a channel. downstream, a tank’s sluice fed gardens and paddy; after rains, men desilted the bund.”

(a) identify the water-lifting device.

(b) name two components of the irrigation network described.

(c) state two effects on agrarian life.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 (a) saqiya (persian wheel).

🔴 (b) channel from well, and a tank with sluice.

🔵 (c) secured double-cropping and garden produce; stabilised village supply and markets, supporting revenue and population.

🔵 Question 33 — source/case (1+1+2)

“the chief will present horses and coin at the yearly audience; on summons he marches with his men. he shall protect markets and canals in his pargana.”

(a) identify the institution.

(b) state one obligation.

(c) explain one way this shaped centre–local relations.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 (a) zamindari within the jagirdari system.

🔴 (b) tribute/payment at audience and military service when called.

🔵 (c) bound local authority to imperial needs, exchanging recognition for service; cooperation sustained order and revenue, while failure risked conflict.

🔵 Question 34.1 (map work): mark and label surat on an outline map of india

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • surat on the gujarat coast, a major export port and mandi drawing cotton and indigo from the interior.

🔵 Question 34.2 (map work): mark and label bayana

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • bayana in present-day rajasthan, an important north indian indigo zone.

🔵 Question 34.3 (map work): mark and label burhanpur

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • burhanpur in the deccan (madhya pradesh/maharashtra border region), a cotton-textile and trading centre.

🔵 Question 34.4 (map work): identify any two marked centres from the key

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • surat — west-coast port funnelling silver and exports.

🔴 • bayana — renowned for indigo cultivation and trade.

💬 vi alternative for q34.1–34.4: list three sites with states—surat (gujarat), bayana (rajasthan), burhanpur (madhya pradesh/maharashtra)—and give one-line significance for any two as above.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

ONE PAGE REVISION SHEET

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

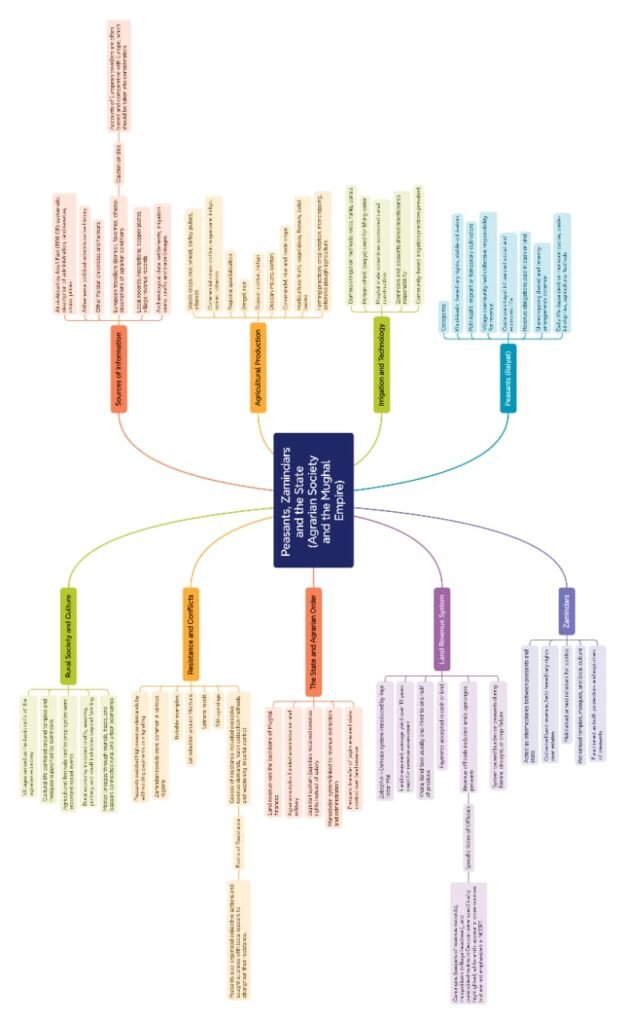

MIND MAPS

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————