Class 12 : History (English) – Lesson 6 Bhakti–Sufi Traditions

EXPLANATION & SUMMARY

A Sufi

🔵 Detailed Explanation

🟢 1. Introduction: The Spiritual Climate of Medieval India

🔵 In medieval India (8th–18th centuries), religion was not static—beliefs and practices evolved.

🟡 Bhakti and Sufi movements arose as inclusive, devotional traditions challenging rigid rituals and social hierarchies.

🔴 These movements bridged Hindu–Muslim cultural worlds, promoting personal experience of the divine over formalism.

💡 Concept: Bhakti (devotion) in Hinduism and Sufism in Islam both emphasized love for God, humility, and social equality.

🟢 2. Early Bhakti Movements (6th–9th centuries)

🔵 Originated in South India among Alvars (Vishnu devotees) and Nayanars (Shiva devotees).

🟡 Alvars composed Tamil hymns (Divya Prabandham) celebrating Vishnu’s grace.

🔴 Nayanars denounced caste barriers and performed acts of service in Shiva’s name.

➡️ Real-life link: Even today, many South Indian temple rituals recite Alvar hymns.

✏️ Note: These saints wandered, sang in the vernacular, and opened temple culture to common people.

🟢 3. Philosophical Foundations of Later Bhakti

🔵 Shankara (8th c.) – Advaita Vedanta: stressed non-dualism—soul and Brahman are one.

🟡 Ramanuja (11th–12th c.) – Vishishtadvaita: emphasized qualified non-dualism, advocating personal devotion to Vishnu.

🔴 Madhva (13th c.) – Dvaita: dualism between soul and God, supporting personal worship.

💡 Concept: These philosophies shaped later Bhakti movements across India.

🟢 4. Regional Bhakti Saints (13th–17th centuries)

🔵 Maharashtra – Sant Tukaram & Sant Namdev: Kirtans (devotional songs) stressed equality and inner purity.

🟡 North India – Kabir: Criticized empty rituals of both Hindus and Muslims; advocated a formless God (nirguna bhakti).

🔴 Rajasthan – Mirabai: Expressed intense personal devotion to Krishna through poetry, often defying social norms.

🟡 Punjab – Guru Nanak: Founded Sikhism, combining Bhakti and Sufi ideals, preaching honest living and oneness of God.

✔️ Impact: Unified communities across caste, gender, and religious lines.

🟢 5. Emergence of Sufism in India

🔵 Sufism—a mystical Islamic tradition—emerged from West Asia, reaching India by the 12th century.

🟡 Sufi orders (silsilas) like Chishti, Suhrawardi, Naqshbandi, and Qadiri established khanqahs (hospices).

🔴 Chishti saints such as Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti (Ajmer) welcomed all people, offering spiritual solace and practical aid.

➡️ Khanqahs functioned as community centers—feeding the poor, mediating disputes, and fostering interfaith contact.

💡 Concept: Sufis stressed zikr (remembrance of God), sama (devotional music), and service.

🟢 6. Shared Spaces and Cultural Syncretism

🔵 Bhakti and Sufi practices often overlapped:

🟡 Pilgrimage sites (dargahs and temples) attracted mixed congregations.

🔴 Devotional music (qawwali, bhajans) borrowed tunes and instruments across traditions.

🟢 Architectural forms fused Hindu–Islamic aesthetics (e.g., tombs with temple motifs).

✏️ Note: Such syncretism softened communal boundaries and enriched India’s composite culture.

🟢 7. Critique of Orthodoxy and Social Order

🔵 Saints challenged caste discrimination and patriarchal restrictions.

🟡 Kabir: “If you are a Brahmin, why were you not born differently?”—a direct rebuke to caste arrogance.

🔴 Mirabai’s defiance of royal expectations highlighted women’s spiritual agency.

✔️ Result: Religious life became more accessible to peasants, artisans, and women.

🟢 8. Devotional Texts and Vernacularization

🔵 Bhakti and Sufi saints composed in regional languages (Hindi, Marathi, Punjabi, Tamil), making religion people-centric.

🟡 Example: Guru Granth Sahib compiles hymns of Sikh Gurus, Kabir, and Sufi saints.

🔴 Vernacular compositions undermined the monopoly of Sanskrit and Persian elites.

💡 Concept: Vernacularization democratized sacred knowledge.

🟢 9. Bhakti under Mughal Rule

🔵 Mughal emperors like Akbar encouraged Sulh-i Kul (universal peace), resonating with Bhakti–Sufi ideals.

🟡 Akbar visited Sufi shrines and invited Hindu saints to court debates.

🔴 Dara Shikoh translated Upanishads and engaged Sufi metaphysics, seeking common spiritual ground.

🟢 10. Differences within Bhakti & Sufi Currents

🔵 Saguna Bhakti (with form) vs. Nirguna Bhakti (formless God).

🟡 Sufi orders varied: Chishtis were inclusive and devotional; Naqshbandis were more orthodox.

🔴 Such diversity shows these traditions were not monolithic.

🟢 11. Political and Social Impact

🔵 Reduced tensions between Hindu and Muslim communities in many regions.

🟡 Gave voice to marginalized groups.

🔴 Their ethical messages influenced rulers and commoners alike.

✔️ Legacy persists in India’s composite culture—festivals, music, and literature still draw from these traditions.

🟢 12. Contemporary Relevance

🔵 Bhakti–Sufi values—tolerance, compassion, equality—remain vital in a pluralistic society.

🟡 Modern devotional music (bhajans, qawwalis) still echo medieval melodies.

🔴 Interfaith harmony movements cite Kabir, Guru Nanak, and Sufi saints as inspirations.

🟡 Summary (~300 words)

🔵 The Bhakti–Sufi movements transformed Indian religious life between the 8th and 18th centuries.

🟢 Early Bhakti in South India (Alvars & Nayanars) emphasized devotion and rejected caste barriers.

🔴 Later Bhakti philosophers like Shankara, Ramanuja, Madhva shaped spiritual thought.

🟡 Saints such as Kabir, Mirabai, Guru Nanak, Tukaram, Namdev brought religion to the common people, critiquing orthodoxy and championing equality.

🔵 Sufism entered India via orders like Chishti and Naqshbandi, establishing khanqahs that welcomed all communities.

🟢 Shared spaces—pilgrimages, music, and architecture—created syncretic cultural forms.

🔴 Devotional texts in vernacular languages democratized religious knowledge, challenging Sanskrit–Persian dominance.

🟡 Under the Mughals, Akbar’s Sulh-i Kul and Dara Shikoh’s translations reflected Bhakti–Sufi ideals.

🔵 While differences existed—Saguna vs. Nirguna Bhakti, inclusive Chishtis vs. orthodox Naqshbandis—both traditions valued love for God over ritual.

✔️ Politically and socially, these movements softened communal divisions, empowered marginalized groups, and influenced Indian culture profoundly.

💡 Today, their messages of tolerance and unity remain relevant for sustaining communal harmony.

📝 Quick Recap

🌿 Origins: Early Bhakti (Alvars, Nayanars) in South India.

⚡ Key Saints: Kabir, Mirabai, Guru Nanak, Tukaram, Namdev, Sufi masters like Moinuddin Chishti.

🧠 Philosophy: Personal devotion > ritual; Saguna vs. Nirguna Bhakti; Sufi mysticism.

➡️ Cultural Blend: Vernacular texts, qawwalis, bhajans, shared pilgrimage sites.

✔️ Legacy: Equality, compassion, and interfaith harmony still inspire modern India.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

QUESTIONS FROM TEXTBOOK

🔵 Question 1: Explain with examples what historians mean by the integration of cults.

🟢 Answer 1 (≈135 words):

🟡 Idea: “Integration of cults” refers to the process by which local deities, rituals, and sacred places were absorbed into larger religious traditions, creating broader communities of worship.

🔵 Mechanisms:

➡️ Identification: Village goddesses were identified with Durga/Parvati; pastoral deities were linked to Krishna/Shiva.

➡️ Mythic weaving: Puranic genealogies wove regional gods into pan-Indian myths, granting them recognised status.

➡️ Temple incorporation: Local shrines were rebuilt as larger temples, receiving endowments and priestly oversight.

🟢 Examples:

✔️ In Tamil country, many amman (goddess) shrines were integrated into Shaiva/Shakta networks.

✔️ Alvar and Nayanar hymns praised regional images as forms of Vishnu or Shiva, drawing diverse castes into common worship.

🔴 Outcome: Integration preserved local identities yet situated them inside shared Sanskritic/vernacular frameworks, fostering cultural cohesion across regions.

🔵 Question 2: To what extent do you think the architecture of mosques in the subcontinent reflects a combination of universal ideals and local traditions?

🟢 Answer 2 (≈145 words):

🟡 Universal ideals (Islamic):

➡️ Orientation to qibla, presence of mihrab and minbar, congregational prayer hall, emphasis on simplicity and a space for collective devotion.

🔵 Local traditions (Indian):

➡️ Use of trabeate (post-lintel) construction, corbelled domes/arches before true arches spread.

➡️ Incorporation of spolia and indigenous motifs (lotus, kalasha, vine scrolls), and jali screens for light and ventilation.

➡️ Region-specific forms: chhatris and multi-cusped arches in the west; jaunpur’s massive pylon-like portals; Gujarat’s delicate stone carving.

🟢 Illustrations:

✔️ Quwwat-ul-Islam (Delhi) adapts local temple pillars within a mosque plan.

✔️ Adina Mosque (Pandua) and Jami Masjid (Ahmedabad) marry universal prayer requirements with regional craft.

🔴 Extent: The result is a hybrid aesthetic—functional universality anchored in regional materials, skills, and symbolism, expressing both the unity of worship and the diversity of Indian art.

🔵 Question 3: What were the similarities and differences between the be-shari‘a and ba-shari‘a sufi traditions?

🟢 Answer 3 (≈140 words):

🟡 Similarities:

➡️ Both sought proximity to God through love, remembrance (zikr), discipline, and a guide (pir) within a silsila.

➡️ Both valued inner purification, service, and ethical conduct.

🔵 Differences:

✔️ Ba-shari‘a (“with the law”): Observed shari‘a rigorously—regular prayer/fasting, sobriety, and adab (proper conduct). Many Chishtis modelled this path, permitting sama with restraint.

✔️ Be-shari‘a (“without the law”): Looser attitude to legal prescriptions; some qalandari/malamati strands embraced antinomian practices, ecstatic expressions, or itinerancy to shun social respectability.

🔴 Public image & regulation: Ba-shari‘a sufis usually enjoyed wider social acceptance and elite patronage; be-shari‘a groups attracted awe and suspicion, prompting juristic criticism.

🟢 UpShot: Both enriched Indian spirituality—the first by normative piety, the second by radical interiority—but they differed in their stance toward law and social conventions.

🔵 Question 4: Discuss the ways in which the Alvars, Nayanars and Virashaivas expressed critiques of the caste system.

🟢 Answer 4 (≈145 words):

🟡 Alvars (Vaishnava) & Nayanars (Shaiva):

➡️ Composed vernacular Tamil hymns accessible to artisans, peasants, and women; devotion (bhakti) not birth became the basis of worth.

➡️ Their hagiographies honour saints from diverse jatis, modelling inclusion in temple spaces and congregational singing.

🔵 Practices that challenged hierarchy:

✔️ Emphasis on prasada, darshan, and collective singing (kirtan) where mixed groups gathered without ritual segregation.

🔴 Virashaivas/Lingayats (Karnataka):

➡️ Rejected ritual pollution rules, brahminical mediation, and emphasised work-ethic and personal devotion marked by the linga.

➡️ Encouraged inter-caste marriage and widow remarriage; opposed ancestor rituals that reinforced lineage superiority.

🟢 Core Critique: All three traditions shifted religious authority from birth status to ethical devotion, community service, and personal experience of the divine, thus undermining caste exclusivity in practice and ideology.

🔵 Question 5: Describe the major teachings of either Kabir or Baba Guru Nanak, and the ways in which these have been transmitted.

🟢 Answer 5 (≈150 words, Baba Guru Nanak):

🟡 Teachings:

➡️ Oneness of God beyond sectarian boundaries; rejection of idolatry and empty ritual.

➡️ Stress on Nam-simran (remembering the Name), honest labour (kirat karo), sharing (vand chhako), and service (seva).

➡️ Social ethics: equality of all castes and genders; condemnation of hypocrisy and exploitation.

🔵 Transmission:

✔️ Sangat–Langar institutions embodied equality through collective prayer and communal kitchen.

✔️ Hymns were sung (kirtan) and memorised, travelling with itinerant singers and disciples.

✔️ Canonical consolidation in the Guru Granth Sahib (compiled later by Guru Arjan) preserved Nanak’s bani; Gurmukhi standardisation by Guru Angad secured stable textual transmission.

🔴 Continuity: Regular recitation, scriptural study, and gurdwara practices sustain his message, influencing broader Bhakti–Sufi ethics of devotion, equality, and service.

🔵 Question 6: Discuss the major beliefs and practices that characterised Sufism. (about 250–300 words)

🟢 Answer 6 (≈280 words):

🟡 Beliefs (doctrinal core):

➡️ Tawhid—absolute unity of God; the seeker strives to efface ego and align the heart with the Divine.

➡️ Ihsan—worship God “as if you see Him,” privileging intention and sincerity over outward show.

➡️ Centrality of the pir–murid (master–disciple) bond within a silsila that traces spiritual authority to the Prophet.

➡️ Many orders (esp. influenced by Ibn al-‘Arabi) affirmed wahdat al-wujud (unity of being), seeing creation as a sign of God’s presence.

🔵 Ethos (adab and akhlaq):

✔️ Humility, patience, generosity, detachment, and service to the poor were practical virtues.

✔️ Tolerance toward other paths and protection of guests/strangers fostered wide appeal.

🟢 Practices (paths to inner purification):

➡️ Zikr (silent or vocal remembrance), muraqaba (meditation), muhasaba (self-accounting), and disciplined fasting.

➡️ Sama—listening to devotional music and poetry—to awaken love and dissolve the ego (permitted with conditions by some, criticised by others).

➡️ Khanqah life—shared meals, menial service, and learning—trained novices in humility and community.

🟡 Institutions and texts:

➡️ Khanqahs/dargahs became centres for relief, counselling, and inter-communal contact; ziyarat (visiting shrines) offered solace and vows.

➡️ Malfuzat (sayings of saints), tazkirahs (biographies), and letters preserved teachings, while qawwali and vernacular poetry diffused them among artisans and peasants.

🔴 Diversity across silsilas:

✔️ Chishtis cultivated inclusion and distance from power; Suhrawardis engaged more with courts; Naqshbandis stressed sobriety and strict law.

✅ Sum-up: Sufism united inner devotion with ethical service, shaping a compassionate, accessible spirituality across the subcontinent.

🔵 Question 7: Examine how and why rulers tried to establish connections with the traditions of the Nayanars and the sufis. (about 250–300 words)

🟢 Answer 7 (≈285 words):

🟡 Why (motives):

➡️ Legitimacy: Rulers drew moral authority from revered saints whose charisma commanded popular trust.

➡️ Integration: Ties with saints facilitated the incorporation of regions, castes, and guilds into stable polities.

➡️ Social peace: Shared rituals around shrines softened tensions and projected rulers as protectors of dharma/faith.

🔵 How (with Nayanars):

✔️ Early Chola kings endowed temples singled out in Tevaram hymns; rebuilding and gifting land/cuvely rights bound agrarian elites and devotees to the crown.

✔️ Processional festivals, irrigation support, and temple-town growth linked royal surplus to Shaiva devotional networks.

🟢 How (with Sufis):

✔️ Delhi Sultans and Mughals visited dargahs (e.g., Ajmer Sharif of Mu‘inuddin Chishti), seeking blessings before campaigns; royal endowments supported langar, wells, sarais.

✔️ Akbar’s frequent ziyarat to Ajmer and grants to multiple khanqahs publicised a policy of sulh-i kul (universal peace).

✔️ Malfuzat recorded saint-king interactions, broadcasting images of pious rule; conversely, some sufis maintained distance to preserve moral independence, which paradoxically enhanced their prestige.

🟡 Consequences:

➡️ Court–saint relations channelled charity, stabilised markets and pilgrim routes, and mediated conflicts.

➡️ Association with inclusive devotional traditions improved rulers’ popular acceptance across religious lines.

🔴 Limits & nuances:

✔️ Not all ties were harmonious—jurists sometimes criticised excess patronage or innovations; some sufis rejected gifts to avoid dependence.

✅ Overall: By aligning with Nayanar temples and Sufi shrines, rulers pursued political consolidation through sacral legitimacy, while saints gained material support and wider reach.

🔵 Question 8: Analyse, with illustrations, why bhakti and sufi thinkers adopted a variety of languages in which to express their opinions. (about 250–300 words)

🟢 Answer 8 (≈275 words):

🟡 Aim: accessibility & intimacy. Saints wanted ordinary people—peasants, artisans, women, lower castes—to understand and remember their message. Vernaculars provided emotional immediacy missing in elite idioms.

🔵 Bhakti illustrations:

✔️ Alvars/Nayanars sang in Tamil, sacralising local landscapes and icons.

✔️ Kabir used sant-bhasha/Hindavi, mixing Hindi-vernacular with Persian/Arabic terms, so both Hindus and Muslims resonated.

✔️ Tukaram/Namdev composed Marathi abhangas; Mirabai sang in Rajasthani/Braj, enabling women’s devotional circles.

🟢 Sufi illustrations:

✔️ While Persian remained an administrative/literary lingua franca, sufis composed qawwalis and verse in Hindavi/Urdu/Punjabi/Sindhi, sung in khanqahs and fairs.

✔️ Baba Farid’s Punjabi verses and later ‘Abd al-Rahman/‘Abdul Quddus’ Hindavi writings bridged audiences.

🟡 Modes of circulation:

➡️ Oral performance (kirtan, sama) ensured retention; chorus-responses helped non-literate devotees participate.

➡️ Manuscript anthologies (e.g., Guru Granth Sahib, bhakti pothis, malfuzat) stabilised texts while retaining musical recitation.

🔴 Why diversity mattered:

✔️ Vernacularisation democratised sacred knowledge, weakened monopolies of Sanskrit/Persian, and promoted social inclusion.

✔️ Multilingual expression mirrored India’s plural society, encouraging inter-communal dialogue and shared ethical vocabularies (seva, daya, prem).

✅ Conclusion: Adopting many languages was a deliberate pedagogy—to reach, move, and reform everyday audiences—thereby ensuring wider diffusion and lasting influence of Bhakti–Sufi ideas.

🔵 Question 9: Read any five of the sources included in this chapter and discuss the social and religious ideas that are expressed in them. (about 250–300 words)

🟢 Answer 9 (≈270 words; thematic analysis, no verbatim quoting):

🟡 (i) Alvar hymn: Celebrates grace and bhakti as the true basis of worth, implicitly challenging caste pride; temple as a home for all devotees.

🔵 (ii) Nayanar (Tevaram) verse: Exalts service to Shiva over birth status; ritual is meaningful only when joined with love and ethical living—a critique of ritualism divorced from morality.

🟢 (iii) Basavanna’s vachana (Virashaiva): Urges personal devotion marked by the linga; rejects pollution taboos, promotes dignity of labour, and allows women and lower castes spiritual agency.

🟡 (iv) Kabir doha: Proclaims a formless God and condemns sectarian quarrels; insists that inner transformation outranks external rites, making space for Hindu–Muslim commonality.

🔵 (v) Sufi malfuzat (e.g., Nizamuddin Auliya): Emphasises compassion, charity, tolerance, and detachment from power; khanqah as a shelter for travellers and the poor, modelling egalitarian practice.

🔴 Cross-cutting ideas:

✔️ Equality: Value of a person lies in bhakti/ishq-e-ilahi, not lineage.

✔️ Ethical devotion: Truthfulness, humility, seva as marks of the spiritual path.

✔️ Critique of orthodoxy: Rituals are validated by intent; empty formalism is rejected.

✔️ Vernacular voices: Use of Tamil, Marathi, Braj, Hindavi, Punjabi expands participation beyond elites.

🟢 Outcome: These sources collectively imagine a community of seekers where caste and gender boundaries soften, inter-faith bridges are built, and everyday ethics become central to religious life—capturing the chapter’s core message of inclusive, experiential devotion.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

OTHER IMPORTANT QUESTIONS FOR EXAMS

🔵 Question 1: The Alvars are best known as poet-saints devoted to

A. Shiva

B. Durga

C. Vishnu

D. Ganesh

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 2: The Nayanars primarily celebrated devotion to

A. Surya

B. Shiva

C. Vishnu

D. Buddha

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 3: Nirguna Bhakti refers to devotion to

A. God with attributes and form

B. Multiple deities simultaneously

C. A formless, attributeless Absolute

D. Nature spirits and ancestors

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 4: The Chishti Sufi order in India is especially associated with

A. Royal service and court employment

B. Strict legalism and political activism

C. Khanqahs open to all and sama (devotional music)

D. Maritime trade networks

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 5 (Assertion–Reason):

Assertion (A): Bhakti and Sufi traditions privileged personal experience of the divine over ritual formalism.

Reason (R): They held that birth-based caste alone determines spiritual eligibility.

A. Both A and R are true, and R explains A.

B. Both A and R are true, but R does not explain A.

C. A is true but R is false.

D. A is false but R is true.

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 6: A khanqah was a

A. Market for luxury textiles

B. Sufi hospice and training centre

C. Court record office

D. Temple treasury

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 7: Guru Nanak emphasised all of the following except

A. Oneness of God

B. Honest labour and sharing

C. Pilgrimage as the only path

D. Remembering the Name (Nam-simran)

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 8 (Match-the-Columns): Match the Sufi order (Column I) with a characteristic (Column II).

Column I: (i) Chishti (ii) Suhrawardi (iii) Naqshbandi (iv) Qadiri

Column II: (P) Sobriety & shari‘a rigor (Q) Court engagement in north-west (R) Inclusive khanqahs & sama (S) Spread in Deccan under saints like Shahul Hameed

A. (i-R), (ii-Q), (iii-P), (iv-S)

B. (i-Q), (ii-R), (iii-S), (iv-P)

C. (i-S), (ii-P), (iii-R), (iv-Q)

D. (i-R), (ii-P), (iii-Q), (iv-S)

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 9: Virashaivas/Lingayats are associated with the early spread in

A. Kashmir

B. Karnataka

C. Bengal

D. Assam

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 10: Vernacularisation in the Bhakti–Sufi context primarily means

A. Replacing all rituals with philosophy

B. Using regional languages for devotional expression

C. Translating only Sanskrit texts into Persian

D. Abandoning poetry for prose sermons

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 11 (Assertion–Reason):

Assertion (A): Many Bhakti and Sufi compositions were designed for oral performance.

Reason (R): Oral forms like kirtan and qawwali enabled participation by non-literate devotees.

A. Both A and R are true, and R explains A.

B. Both A and R are true, but R does not explain A.

C. A is true but R is false.

D. A is false but R is true.

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 12: Mirabai’s poetry primarily expresses devotion to

A. Shiva

B. Krishna

C. Rama

D. Hanuman

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 13 (Chronology/Order): Arrange the following figures in correct chronological order (earliest to latest):

Shankara 2. Ramanuja 3. Madhva 4. Guru Nanak

A. 1-2-3-4

B. 2-1-3-4

C. 1-3-2-4

D. 2-3-1-4

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 14: The Guru Granth Sahib contains hymns of

A. Only the ten Sikh Gurus

B. Sikh Gurus and selected Bhakti/Sufi saints

C. Only Persian Sufi poets

D. Only Alvar hymns

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 15 (Match-the-Columns): Match the saint (Column I) with the associated region (Column II).

Column I: (i) Tukaram (ii) Kabir (iii) Nizamuddin Auliya (iv) Andal

Column II: (P) Delhi (Q) Maharashtra (R) Varanasi (S) Tamil region

A. (i-Q), (ii-R), (iii-P), (iv-S)

B. (i-R), (ii-Q), (iii-S), (iv-P)

C. (i-Q), (ii-P), (iii-R), (iv-S)

D. (i-S), (ii-R), (iii-Q), (iv-P)

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 16: Sama in Sufi practice refers to

A. Juristic reasoning

B. Remembrance by silent meditation

C. Devotional audition/music

D. Ascetic fasting

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 17 (Assertion–Reason):

Assertion (A): Some Sufi orders discouraged close ties with rulers.

Reason (R): Distance from political power protected moral authority and public trust.

A. Both A and R are true, and R explains A.

B. Both A and R are true, but R does not explain A.

C. A is true but R is false.

D. A is false but R is true.

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 18: Saguna Bhakti most closely aligns with devotion to

A. A formless Absolute

B. Deity with attributes and iconography

C. Elements of nature only

D. Ancestral spirits

🟢 Answer: B

🔵 Question 19 (Picture/Item ID — text alternative): Identify the site described — “A famous Sufi dargah at Ajmer associated with Mu‘inuddin Chishti.”

A. Haji Ali Dargah

B. Nizamuddin Dargah

C. Ajmer Sharif Dargah

D. Baba Farid’s Dargah

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 20: A key social idea shared by many Bhakti and Sufi thinkers was

A. Birth determines access to God

B. Only Sanskrit/Persian can convey sacred truth

C. Ethical living and love of God over ritual status

D. Military service as the path to salvation

🟢 Answer: C

🔵 Question 21 (Assertion–Reason):

Assertion (A): Mughal patronage enhanced the visibility of certain Sufi shrines.

Reason (R): Imperial endowments supported langar, wells, and sarais for pilgrims.

A. Both A and R are true, and R explains A.

B. Both A and R are true, but R does not explain A.

C. A is true but R is false.

D. A is false but R is true.

🟢 Answer: A

🔵 Question 22: Explain how vernacular languages helped popularise Bhakti teachings.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • Vernacular hymns (Tamil, Marathi, Braj, Punjabi) made doctrine intelligible to non-elites.

🔴 • Oral performance in kirtan and qawwali enabled collective singing, memorisation, and emotional bonding.

🔵 • Local idioms and place-names sacralised everyday life, drawing artisans, peasants, and women into devotional communities.

🔵 Question 23: State three functions of a khanqah in medieval India.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • Spiritual training under a pir with zikr, discipline, and ethical conduct.

🔴 • Social welfare via langar, water, and lodging for travellers and the poor.

🔵 • Mediation and cohesion by resolving disputes and fostering inter-communal contact.

🔵 Question 24A (Attempt any one): Differentiate Saguna and Nirguna Bhakti.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • Saguna: devotion to personal deities with form (Rama, Krishna); temple worship, images, festivals.

🔴 • Nirguna: devotion to a formless Absolute; emphasis on interiority and the Name; often critiques ritual.

🔵 • Both value love and ethical life, but differ on form/icon and ritual emphasis.

🔵 Question 24B (Attempt any one): Mention three ways Virashaivas/Lingayats challenged caste practices.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • Rejected ritual pollution rules and priestly mediation.

🔴 • Encouraged inter-caste unions and widow remarriage.

🔵 • Stressed personal devotion (linga), dignity of labour, and community equality.

🔵 Question 25: How did rulers use connections with Bhakti/Sufi traditions?

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • Sought legitimacy via temple endowments and shrine visits.

🔴 • Supported festivals, repairs, pilgrim routes to project moral authority.

🔵 • Public association with inclusive devotion signalled sulh-i kul and broadened acceptance.

—

🔵 Question 26A (attempt any one): explain the idea of sulh-i kul and its relevance to Bhakti–Sufi landscapes

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • sulh-i kul means universal peace: a policy of equal regard for communities, promoting public order through tolerance.

🔴 • it resonated with inclusive shrine cultures (khanqahs, shared festivals), easing tensions and widening imperial legitimacy.

🔵 • practical forms included grants to shrines, sarais, wells, and facilitating pilgrim routes, signalling ethical kingship.

🔵 Question 26B (attempt any one): list three features of the Naqshbandi order in India

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • emphasis on sobriety, silent zikr, and close adherence to shari‘a.

🔴 • scepticism toward sama and some shrine practices; preference for inward discipline.

🔵 • occasional proximity to power in the Mughal period (e.g., reformist counsel), framing a legally grounded piety.

🔵 Question 27: state three reasons many saints critiqued ritualism

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • rites without inner sincerity were seen as hollow; intention and love mattered more.

🔴 • ritual barriers upheld status hierarchies; devotion should be open to all regardless of birth.

🔵 • turning to ethical action (seva, honesty) and remembrance of the divine redirected focus from display to transformation.

🔵 Question 28A (attempt any one): evaluate how Bhakti–Sufi traditions critiqued social hierarchy and reshaped everyday religiosity

🟢 Answer:

🟡 introduction: between the 8th–18th centuries, devotional currents redirected religion from ritual status to ethical love of God, unsettling caste and gender barriers.

🔴 equality in access: alvars, nayanars, and kabir affirmed that devotion outweighs birth; prasada, kirtan, and congregational singing normalised mixed-status presence in sacred spaces.

🔵 women’s agency: voices like mirabai expanded sacred authorship, challenging seclusion and demonstrating publicly enacted devotion.

🟢 sufi inclusivity: khanqahs welcomed travellers and the poor; langar and hospitality turned service into worship, softening communal boundaries.

🟡 vernacular turn: tamil, marathi, braj, and punjabi hymns democratised sacred speech and mapped local landscapes into sacred geographies.

🔴 ethics over form: nirguna strands and many sufis critiqued empty formalism; even saguna streams linked piety to conduct.

🔵 public culture: processions, fairs, and ziyarat created shared arenas where music and feeding forged solidarities.

🟢 outcome and legacy: while hierarchies persisted, ideals shifted toward dignity of labour, humility, and mutual respect, leaving a durable imprint on composite culture.

🟠 conclusion: by wedding interior devotion to social ethics, these traditions offered humane frameworks for everyday religiosity.

🔵 Question 28B (attempt any one): explain the processes of integration of cults and their significance for hindu traditions

🟢 Answer:

🟡 introduction: integration describes how local deities and rites were absorbed into wider shaiva, vaishnava, or shakta frameworks without erasing local identity.

🔴 mythic weaving: puranic genealogies identified village goddesses with durga/parvati or pastoral heroes with krishna, granting pan-indian recognition.

🔵 temple incorporation: small shrines were rebuilt as larger temples with endowments; festivals and processions linked hamlets and markets into pilgrimage circuits.

🟢 liturgical synthesis: vernacular hymns praised local images as universal forms while sanskrit rites coexisted with regional practices.

🟡 social effect: shared worship eased inter-caste mingling and strengthened agrarian solidarities.

🔴 doctrinal elasticity: philosophies like vishishtadvaita validated loving devotion to a personal god, harmonising metaphysics with popular practice.

🔵 political mediation: rulers endowed integrated temples, stabilising irrigation, crafts, and revenue while converting sacred charisma into legitimacy.

🟢 conclusion: braiding local cults into wider traditions produced a layered pantheon and resilient ritual networks.

🔵 Question 29A (attempt any one): compare chishti, suhrawardi, and naqshbandi orders in india—their ethos and social role

🟢 Answer:

🟡 chishti: love, humility, service; khanqahs with langar; use of sama with restraint; distance from court to preserve moral authority; inclusive shrines (ajmer, delhi).

🔴 suhrawardi: greater openness to state engagement; legal-scholarly orientation; organisational discipline; active in the north-west; bonding with urban elites and ulema.

🔵 naqshbandi: sobriety, silent zikr, strict shari‘a; some political proximity and reformist critiques; sceptical of musical audition.

🟢 social role: all offered spiritual training, mediation, and charity; differing stances toward power and performance created multiple models of piety for varied publics.

🟡 outcome: diversity within sufism broadened reach from popular shrine cultures to legally inclined elites while keeping a core of God-centred ethics.

🔵 Question 29B (attempt any one): assess how mughal policies interacted with Bhakti–Sufi landscapes

🟢 Answer:

🟡 universal peace (sulh-i kul): akbar’s engagements with shrines and communities framed a public ethic of tolerance.

🔴 patronage: grants to shrines, sarais, wells, and pilgrim routes enhanced welfare and mobility; ziyarat to ajmer amplified shrine prestige.

🔵 intellectual traffic: translations (e.g., dara shikoh’s interest in upanishads) and debates signalled cross-tradition curiosity.

🟢 ambivalences: some naqshbandis critiqued innovations; jurists worried about syncretism, indicating negotiation rather than uniform harmony.

🟡 result: imperial–saint interactions stitched political legitimacy to sacred charisma while some sufis kept principled distance.

🔵 Question 30A (attempt any one): discuss the vernacular revolution in Bhakti–Sufi compositions and its cultural impact

🟢 Answer:

🟡 premise: shifting to regional tongues re-scaled sacred discourse for mass audiences.

🔴 access and memory: tamil, marathi, braj, and punjabi songs in kirtan/qawwali enabled participation and mnemonic retention.

🔵 local sacrality: hymns mapped rivers, groves, and towns into sacred geographies, fusing devotion with daily life.

🟢 plural publics: mixed congregations forged shared emotional repertoires, tempering sectarian difference.

🟡 text and performance: canonical compilations (e.g., guru granth sahib) stabilised bani while keeping it auditory; pothis and malfuzat preserved sayings and counsel.

🔴 legacy: modern folk and film genres echo these cadences; vernacularisation remains a cultural common sense for spirituality.

🔵 Question 30B (attempt any one): explain how women mystics (e.g., mirabai, andal) expanded devotional possibilities

🟢 Answer:

🟡 breaking scripts: mirabai’s refusal of courtly norms and andal’s visionary poetry announced women as theological actors.

🔴 voice and community: songs circulated in women’s circles and public festivals, authorising female agency within bhakti.

🔵 imagery and intimacy: bridal and mystical metaphors legitimated personal intimacy with the divine, bypassing male intermediaries.

🟢 social ripple: honouring women saints opened liturgical roles and defended devotional choice; their hymns still animate temple and kirtan traditions.

🔵 Question 31 — source

“ritual pride builds walls; the name melts them. the beloved is not in the market of vanity but in the heart that serves.”

(a) identify one practice critiqued in the source.

(b) what spiritual method is recommended?

(c) explain how this view promotes social equality.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 (a) empty ritualism and ego are critiqued.

🔴 (b) remembrance of the name with service.

🔵 (c) locating the divine in inner devotion and ethical action detaches access from birth or ritual status, enabling equal participation.

🔵 Question 32 — source

“the doors of the hospice remain open. the traveller and townsman eat together; the stranger is kin.”

(a) name the institution described.

(b) state one practice that embodies this ideal.

(c) give two effects on community relations.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 (a) a sufi khanqah with langar.

🔴 (b) shared meals and hospitality regardless of status.

🔵 (c) builds trust across communities and reduces status barriers, modelling cooperation.

🔵 Question 33 — source

“she sings of the dark one in the streets and courts alike; kin rebuke, but her feet follow the flute.”

(a) identify the saintly figure implied.

(b) what norm is being challenged?

(c) explain one religious message of this stance.

🟢 Answer:

🟡 (a) mirabai.

🔴 (b) patriarchal or royal seclusion norms.

🔵 (c) personal bhakti overrides social constraints; sincere love for God legitimises public devotion by women.

🔵 Question 34.1 (map work): mark and label ajmer on an outline map of india

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • ajmer in rajasthan; associated with the dargah of mu‘inuddin chishti.

🔵 Question 34.2 (map work): mark and label pandharpur on an outline map of india

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • pandharpur in maharashtra; varkari bhakti centre dedicated to vitthala.

🔵 Question 34.3 (map work): mark and label vrindavan on an outline map of india

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • vrindavan in uttar pradesh; a major krishna bhakti site.

🔵 Question 34.4 (map work): identify any two marked centres from the key provided

🟢 Answer:

🟡 • ajmer — chishti sufi shrine.

🔴 • pandharpur — varkari pilgrimage.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

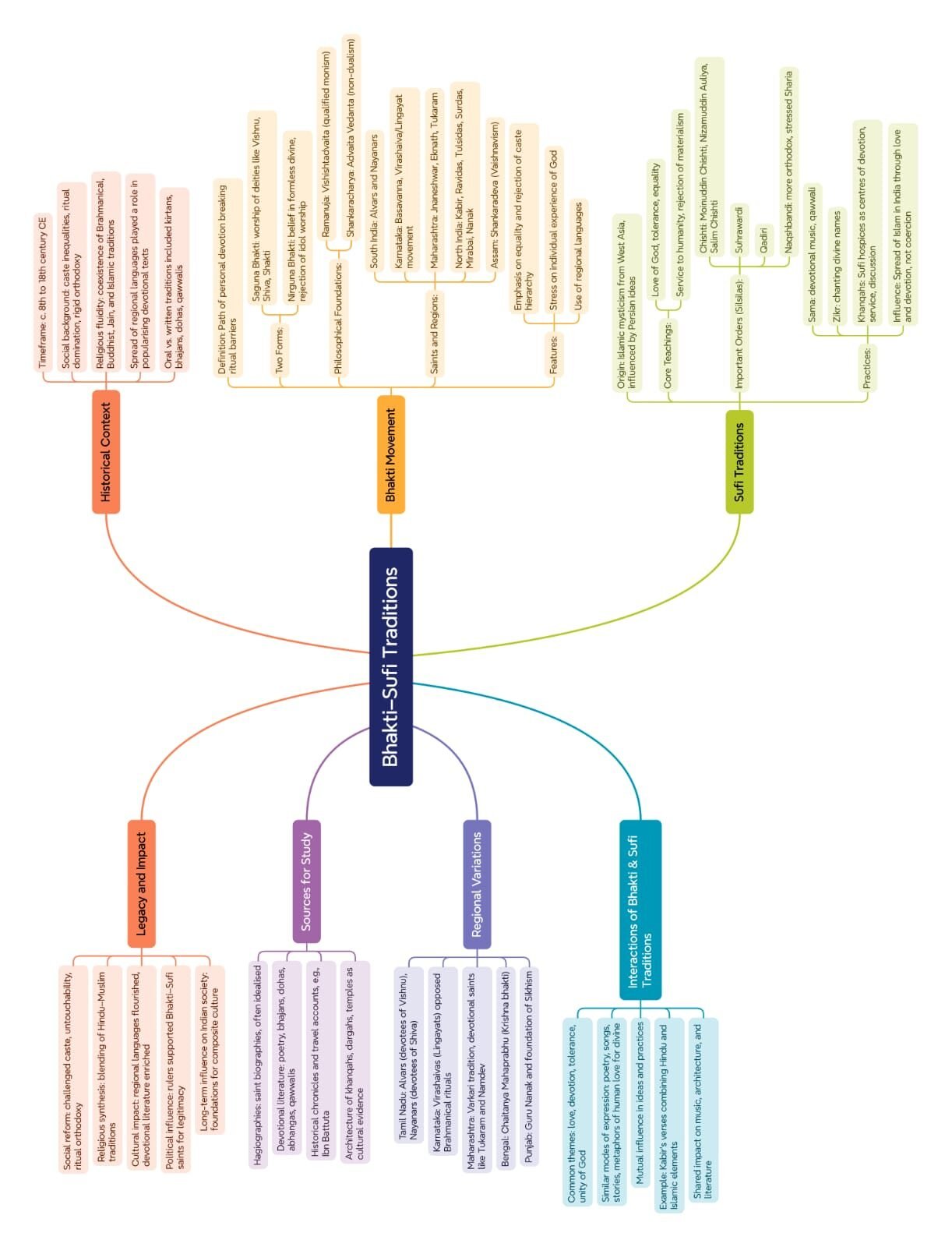

MIND MAPS

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————